The Woodfin Whitewater Wave, North Carolina’s ‘Wave’ of the Future

Currently in development, the Woodfin Whitewater Wave will be one of the more ambitious projects the region has seen.

In 2010, Asheville-based plastic pipe manufacturer Silver-Line Plastics donated a five-acre parcel of land. That real estate happens to be situated on the French Broad River in Woodfin, North Carolina, a few miles north of – and downriver from – Asheville. The company’s gift set in motion a plan of grand scale that is now slated to incorporate a park, an extension of an existing greenway network and – most unusual and ambitious of all – a man-made facility called the Woodfin Whitewater Wave.

Describing himself as a “lifelong outdoor adventurer and whitewater paddler,” Marc Hunt was an early advocate for the Woodfin Wave. “I had seen and experienced the community benefits of in-stream whitewater parks in other locales,” he says. And he explains he became certain of the advantages of one on the French Broad River. Early efforts toward building support for a man-made wave at Jean Webb Park in Asheville’s River Arts District failed to gain traction, so when Hunt learned that nearby Woodfin was gearing up for its own major greenways and parks initiative, he approached the town leaders. “I felt there might be a lot of synergy,” he says. “Turns out there is.”

Hunt points to the success of more than two dozen similar projects across the U.S. “The communities that have developed them rave about the positive impacts,” he says. He formed a group to help build support for a man-made whitewater attraction in Woodfin. Friends of Woodfin Greenway & Blueway was initially led by Hunt; eventually the organization’s efforts were folded into the larger fundraising and outreach activities or RiverLink. That local advocacy group has a stated mission of “promoting the environmental and economic vitality of the French Broad River and its watershed.”

RiverLink Executive director Garrett Artz says that the project fits well with his organization’s larger goals. “We see this not only as a project that furthers how we do our mission, but also as a capacity-building initiative so that we have the skills to replicate riverfront revitalization in many more communities.” And he believes that the Wave’s appeal will extend beyond paddlers. “Even if you don’t jump onto the Wave, it will be a major attraction to be a spectator,” he says.

When the idea of a man-made whitewater run in Woodfin was first floated, opinions were mixed. Though “real” whitewater runs exist along the French Broad and other rivers in the region, a project like the Wave has few local precedents. A $4.5 million bond was put onto the ballot for voters in Woodfin to vote upon in November 2016. While the bond also included sidewalks and a greenway – and was tiny in comparison to bonds on the ballot a few miles away in Asheville – it remained controversial.

“If we were as big as the city of Asheville it would be one thing,” Woodfin Alderman Ronnie Lunsford told the Asheville Citizen-Times‘ Joel Burgess ahead of the vote. “But we’re borrowing almost twice as much as our budget is.” When the town’s Board of Aldermen took a vote on placing the bond on the ballot, two of the six votes were against. Speaking today about his “no” vote, alderman Don Hensley defends his position. “The amount [was] equal to about one year of the town’s budget,” he says, “and I considered it a significant amount for a town the size of Woodfin.” Passage of the bond would have meant a property tax increase for town residents averaging $112 annually.

Other town leaders and personnel were more enthusiastic, right from the start. Today, Woodfin Town Administrator Jason Young says, “I’m more convinced than ever. I think that it’s a way for Woodfin to create a major recreational facility for our citizens.” Pointing out that the town hasn’t borrowed money for the project, he says that the greenway/blueway will “spur growth and redevelopment along a part of the River corridor that hasn’t entirely benefited from the reinvestment in the French Broad.” The Woodfin White Water Wave portion of the project was estimated by the town to cost $2 million, but Hunt placed his estimate closer to $1.6 million.

The bond passed overwhelmingly; even some of the project’s boosters were surprised. “Perhaps the biggest moment came with the 71% approval of the bond referendum,” Hunt says. “In Woodfin, political views tend to be conservative and anti-tax.”

The Wave will be part of a public park facility, free and open to the public, so it won’t directly generate revenue in the form of fees. But advocates point to similar projects and insist that the project will contribute to the region’s economy. Hunt makes the point that a number of water sports related companies are based and/or do significant in the region. “Think ENO, Diamond Brand, Industry Nine, LiquidLogic Kayaks, Astral Designs, and Watershed,” he says. “And,” he adds, “property values have risen markedly since the project was announced.”

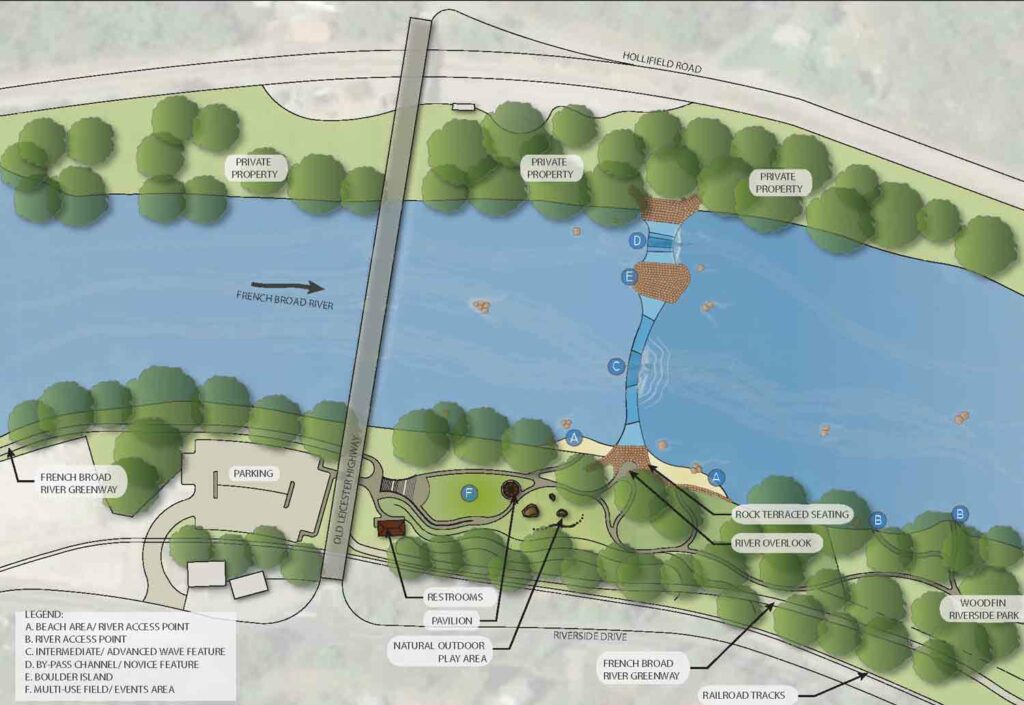

As Emily Patrick reported in a Citizen-Times article from May 2017, the Town of Woodfin moved quickly after the referendum to get started on parts of the larger initiative. Those efforts included purchase of land on Riverside Drive that would allow eventual construction of a building to house bathrooms and other uses. According to that story, the overall plan includes “a pavilion with a stage and a lawn for picnicking, a playground, river access, and a boardwalk over a wetland.”

Patrick’s story provided additional insight into the disposition of the Wave itself. She quoted Woodfin Mayor Jerry Vehaun as saying “a fundraising initiative for a nearby whitewater wave park where kayakers can ride man-made rapids should begin later this summer,” adding that the town was exploring a long-term partnership with the Buncombe County Tourism Development Authority to access additional funds for both the greenway and Wave.

The entire project has grown in scope since its original conception, and those changes have meant delays. But Young believes the benefits outweigh the slower pace. “Since we began this process, it has continued to grow in size in scope into a project well beyond our initial expectations,” he admits. “The project has moved more slowly than any of us had intended,” Hunt admits. “Projects like this are challenging to implement, and it’s the largest infrastructure project ever for the tiny town of Woodfin.”

Both Young and Hunt are convinced that public support for the Wave and other improvements has increased since the bond referendum. “If anything,” Young asserts, “I believe that support has grown over time as people have become more educated about the project.” Hunt agrees. “As we had hoped, the project has become strongly embraced by the community.”

Displaying the sort of guarded pragmatism one expects from a politician – especially one serving a community where many constituents and pols know each other personally – Hensley says that “once the bond passed, my focus [became] one of getting started on the project.”

In May 2019 the Weaverville Tribune published a story by Bejamin Cohn. That article included an update on the project. Noting that half of the budgeted amount for the entire project (including the greenway and other improvements) had been spent, Young was quoted as saying that the project was “as expected, just under budget.”

That same story reported on a presentation made to the town by Linda Giltz, a contractor hired to help Woodfin secure a grant. “Soon after Giltz’s report,” Cohn wrote, “the board voted unanimously in favor of adopting the proposed Parks and Recreation master plan and to approve a grant application for the Parks and Recreation Trust Fund which, if approved, would grant the town $300,000 for park improvements.”

Giltz says that the larger project including the Wave is effectively part of an even grander plan. “Asheville is completing a large project redeveloping the roadways and riverfront, referred to as RADTIP,” she says. “The Woodfin Greenway and Blueway will connect to the RADTIP greenways and parks in the next three to five years and that will create close to 20 miles of continuous greenways.”

Scott Shipley is the principal and lead designer at S2o Design and Engineering; Hunt began consulting with him about the proposed Wave early on. Designer of the U.S. National Whitewater Center in Charlotte, three-time Olympic athlete Shipley brings to the project a background as a professional racer and river engineer with a specialty in whitewater parks. He’s also responsible for projects similar to the one planned for Woodfin: the Eagle River Whitewater Park in Colorado and another in New Zealand.

He says that detailed research and soliciting of public input reinforced his belief that Woodfin is the right spot for the whitewater project, and that the location has a number of advantages. “It’s near a school with kayaking programs, and it’s just upstream of a lake that allows for easy recovery. There is existing parking, trail access, and community pavilions, so this design could be a benefit to the community, and not just the paddling folks.”

Hunt provided a graphical timeline that sets out the schedule for the entire project. The conceptual design and feasibility study phase of the project commenced in the first quarter of 2017 and continued through September of that year. Beginning in the third quarter of 2019, the second phase of the project’s conceptual design will soon get underway. Planned as simultaneous with that are both acquisition and initial conceptual design of the related Riverside Park expansion and improvements project. Those tasks are scheduled to continue through the end of the year.

According to that timeline, the first half of 2020 will see formal requests for proposals, along with selection and engagement of a contractor for the project. Detailed design and permitting – the lengthiest phase of the project – is slated to commence in the third quarter of 2020, continuing through early 2022. Another round of RFPs (this time for actual construction of the Wave) is scheduled for the second and third quarter of 2022. Construction of the Wave itself is planned for the fourth quarter of 2022. While projects of this scale – despite the best, most educated projections – sometimes tend to take longer than anticipated, the Woodfin Wave timeline doesn’t provide for a great deal of wiggle room: Bond funds expire in the fourth quarter of 2023.

Shipley concedes that there are structural challenges involved. “There is development very close to the river, there is flooding, and there’s debris,” he says. “Many of the things that you would normally take for granted are just different in a river that is as wide, flat and ‘bedrocky’ as the French Broad.”

Marc Hunt provides some numbers regarding the projected number of visitors to the proposed park and its whitewater component. Cautioning that the Wave itself “is a very specialized amenity that requires developed skills to use,” he nonetheless estimates “over 400,000 annual users of greenways that relate to the project, and over 15,000 users on the Wave.”

The Buncombe County Tourism Development Authority is providing $2.25 million via the Tourism Product Development Fund grant program. Authority CEO Stephanie Brown says that the project meets her organization’s criteria even though it’s not a direct revenue generator. “Legislation requires that funds are used for capital projects that attract overnight visitors to Buncombe County,” she says. “Projects are evaluated for room night generation rather than revenue.”

Young provides the latest update on the Wave and related projects. He says that the Town of Woodfin is “preparing to finalize [the] contract to move forward with construction of Silver-Line Park and is currently in the process of obtaining the first half of the bond proceeds.” He notes that Woodfin is also negotiating to buy additional property along the French Broad for expansion of park facilities.

Meanwhile, he says, “Were almost ready to start moving dirt.”

# # #